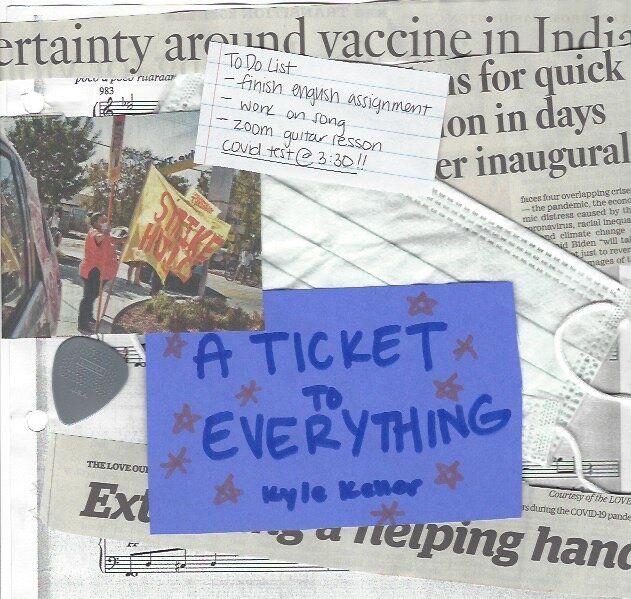

A Ticket to Everything

Collage by Anya Ernst

In the age of the coronavirus, I find myself hanging on to concert memories like an ex’s old t-shirt. Sometimes, late at night, I’ll lock in my earbuds, close my eyes, and harken back to the IDLES show in LA with the kindest, angriest pit I’ve ever been in; the 7-hour endurance test that was OC’s Blivet Bash (where I downed three ketchup packets and liked it); the Pinegrove show in San Diego, two hours prior to which I rode my Razor scooter solo around the downtown area and over the course of which I realized I had a nasty, miserable cold. They are diamonds in the rough of the day-to-day where all the things that excite me most as a young person come to a head — lightning bolts of memory that I’ll be thinking about for the rest of my life. Nowadays, my friends and I are constantly comparing notes on our show withdrawals. It’s silly, in a way, but the root of this microsuffering is a longing for unusual experiences, for community, for casual closeness.

Even longer than I’ve been going to shows, though, I’ve been watching online live performances. And I don’t just mean the live-streamed ones you have to pay for. I mean the free ones — the Tiny Desks, the Audiotrees, the KEXPs, the COLORS shows, the thousands of high-quality concert movies or radio tapings or DIY field recordings floating around on the Internet. They, too, have their memories. I can recall the first time I ever listened to King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard on KEXP’s 2018 live session (where my mind was blown barely thirty seconds into the first track), the day I spent watching “Pinegrove - Dotted line @ Levon helm” over and over and over again just for the moment where Evan Stephens Hall screams the lyric “...I lift my head up / Where beyond my window a thread of light lives,” the countless times I’ve swooned to Shakey Graves’ sweltering, stunning Audiotree performance of “Roll the Bones.” If anything, these moments are stronger because I can go back and relive them — I have a folder in my Bookmarks Bar stuffed with videos that inspire me. I consult it almost daily.

For this reason and others, there’s never been a better time to be a young musician. Artists have to surround themselves with the material they want to create, and we’re lucky enough to live in a time where a person putting tunes together has more access to inspiration, hard-won knowledge, and good role models than anyone’s ever had. This cannot be overstated.

However, over time, I’ve realized that, specifically for a young musician, the emotional effects of consuming this content aren’t limited to joy. Envy, self-hatred, and hopelessness are also ingredients in my constant exposure stew — stronger on bad days, of course, but even on the good ones, they linger just out of sight. There are hundreds of millions of us who are convinced that part of our life’s meaning is to put something into the world — an album, a book, a painting — that, in some way, changes someone’s life. Some of us have done it. Most of us haven’t, or never will. For several reasons (capitalism among them), this element of “some win, some don’t” has turned artistry into a competition, a battle of luck, persistence, and determination with defined winners and losers. If you want to make a career out of being an artist, we’re told, you have to beat all the other guys. You have to be among the best.

That’s where the envy comes in. When our heroes do their jobs on screen, even when they screw up, they seem natural and perfect and permanent in a way we might never be. We don’t get to see the self-inflicted torture that is intrinsic to the creative process; instead, we’re drowned in videos of people doing the things we want to do very well, and when we hold ourselves to that standard, it can be enough to incapacitate us.

“Hasn’t this always been the case?” one could say. “You would feel the same way listening to Jimi Hendrix shred from a stereo in the 70s. Constantly comparing yourself to the masters has been a part of the work for centuries.” That’s definitely true — I’m sure every musician growing up in the late 20th century has memories of rewinding tapes (or CDs, or records, or whatever) over and over again to catch that one solo, or riff, or verse that makes them want to throw their instrument into the garbage — but never before has this faux flawlessness been so abundant, so high-quality, and so paywall-free. As the Internet security mantra goes, when you have access to everything, everything has access to you — in this case, the “everything” will access you right back, warping your perception of your own abilities and self-worth. It doesn’t help that in the same search engine you use to find online performances, you can scroll through Wikipedia articles, learn what the musician was up to when they were your age (the answer is always more), parse interviews, scour social media pages, burrow through the bottomless Internet bucket to find that one nugget that’ll make you feel good about where you are in your journey.

Unfortunately, that nugget doesn’t exist. The arts industry can make a person seeking to succeed in it feel devastatingly tiny, part of an endless milling crowd. And maybe, to some extent, that’s a good thing: one of the most important lessons a human being can learn in their time on Earth is that we’re all hopelessly insignificant — no one is special. But art relies on the illusion of specialness. If we don’t have that little voice in our heads telling us (and often deceiving us into thinking) that we have something that only we can say, we won’t say anything. Putting art into the world is half the work it takes to make something and half the mind-blowingly naïve courage it takes to announce, “I think people should pay attention to this.” No one has to pay attention to you — most of the time, they won’t, and you’re going to be speaking to an empty room. But without these constant, usually ill-fated leaps into the unknown, the greatest art cannot be born.

One of the worst parts of being an artist is that nothing will ever make us feel good about that leap. The leap sucks. In fact, the very process of creating and publicizing art in today’s world seems tailor-made to make us spend too much time worrying and not enough time working. The golden age of online live performance has proven that even the good things — the works that inspire us to create in the first place — have the capacity to prevent us from taking the creative plunge. We must consume the things we love, even become obsessed with them: it’s more reckless to ignore this incredible resource than it is to embrace it. But, by no fault of its own, the digital vault has become a double-edged sword that becomes sharper the more you wield it.

Some days, when I tune into a Tiny Desk or pop on a KEXP session, I just feel inspired. Occasionally, I can barely hit pause fast enough before I’m hustling out to the garage with my guitar and a notebook, ready (and in fact eager) to take the wild, blind leap and see what I find. These days are getting rarer and rarer, though. I like to think of myself as relatively unconcerned with success, but in comparing the number of days I spend absorbed in my craft and the number of days I spend wallowing in self-pity, I’ve come to realize that I’m obsessed with it. It’s started to pervade the act — not the hierarchy, not the pursuit, the raw act — that makes me feel most human. I need to do better at not caring what everyone around me is doing. I need to do better at being worse.

In the life of an artist, there will always be moments where one feels like they’re falling behind in a race, and there’s no way they’ll be able to make up the distance before the finish line. The key is to put on your blinders. To realize that we’re all impossibly foolish and impossibly brave to do what we do. And to just keep doing it.